Main >

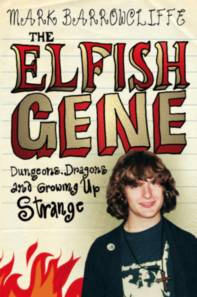

The Elfish Gene (excerpt)

The

following is an excerpt from Mark Barrowcliffe's book The

Elfish Gene: Dungeons, Dragons, and Growing Up Strange. For

more information on the book, click

here.

Chapter 13: An Unexpected Party

Chapter 13: An Unexpected Party

‘Is

it OK if I have a few friends over to wargame today?’ I asked my mum as

I ate my breakfast.

‘How

many?’ said my mum.

‘About

20,’ I said.

‘Fine,’

said my mum, ‘when are they coming?’

‘At

about 11,’ I said.

My

initial suggestion to start the game at 9 was deemed too early by some

of the older boys.

‘Do

you want me to do them any food?’ said my mum.

‘Some

scones would be nice,’ I said.

‘Scones

for 20, three each, 60 scones,’ said my mum, ‘sandwiches too?’

‘Yes

please,’ I said.

My

family were quite capable of having long and angry arguments about

nothing at all, though things like this never seemed to faze us.

I’d

already set aside, in my mind, the whole of the downstairs room, which

luckily my Dad had just knocked through, along with my brothers’

bedroom for the games. I hadn’t actually asked my brothers whether they

minded but I hoped they might be out.

If

the worst came to the worst, I thought, we could fit a few gamers into

the bathroom and anyone who wanted to go to the loo would have to use

the one outside.

At

10.30 I feared no one was coming. At 11.30 my fears were allayed.

Rather than too few boys turning up too many had. Several had brought

brothers and friends. All in all I think we had about 30 boys round

that day, gaming in the lounge, my brother’s bedroom and my parents

bedroom. Scone production went into overdrive.

The

whole house was given over to Dungeons and Dragons, in fact the whole

house was a dungeon. As a game it would have gone like this:

‘On

approaching the front door you can hear the cries of excited voices

from within. What do you do?’

‘I

ring the bell.’

‘The

door is answered by a boy of about 12. He is wearing a home-knitted

jumper and looks keen to return to whatever he was were doing before.

Before you can explain who you are he says, ‘come in, there’s a game

just starting in the upstairs bedroom. Close the door after you.’ Then

he disappears back inside the house. What do you do?’

I

enter the house and follow him.

‘He

goes into a long living room. Ten boys are sitting at a dining table.

It’s been extended but still can hardly contain them all. They are

speaking in an animated way, rolling dice and poring over books and

charts. They do not notice you. What do you do?’

‘I

go out of the room and up the stairs.’

‘You

reach a landing. There are four rooms projecting from it. One is

clearly a bathroom. Closer inspection will reveal that it does indeed

have the chicken tiles - a marble-effect tile that appears to have a

chicken in the pattern, and the avocado suite of the day. What do you

do?’

‘I

enter the second door on the right.’

‘Inside

are about eight boys sprawled around a large double bed. There is a

dressing table and a mirror and fitted cupboards.’

‘Is

there anything unusual about the room?’

‘It

is too small for so many boys. It looks more suitable as sleeping

quarters for a married couple. Lots of the bedroom’s ornaments are

spread across the bed.’

‘I

ask the boys what they are doing with the ornaments.’

‘One

gestures to a vase and says: “That’s the temple of Mordragar, the make

up compact’s the entrance to the sewers, the glass animals are aliens

and the various heirlooms represent spaceships.’

As

I recall the boys in my mum’s bedroom were playing Traveller, a variant

of D&D set in space and cashing in on Star Wars mania. This was

the first time I met Adrian Smith or Chigger as he was known.

Throughout this book I’ve tried to put myself in the shoes of the older

boys I was describing. I’m very aware that any unpleasant behaviour

they exhibited towards me may largely have been because I was unusually

irritating, even for a 12 year old. I’ll do the same for Chigger.

However, I do feel moved to point out that Chigger wasn’t Adrian’s real

name, it was a nickname given to him at school during a biology lesson.

Apparently a Chigger is a sort of burrowing beetle larva that gets

under the skin.

‘Very

few creatures can cause as much torment for their size as the tiny

chigger,’ said the teacher. And so Adrian got his name.

Chigger

was two years older than Billy and in the sixth form at a grammar

school outside of Coventry. He was quite small for his age, pale,

heavily freckled and had bright red hair which he wore slightly long,

giving his head the appearance of a fuse box someone had taken a hammer

to. At the time we were using physical appearance charts from the

independent D&D supplement The Arduin Grimoire. By shaking dice

we could determine what our character looked like, hair colour,

birthmarks, eye colour. If I had diced a character that came up looking

like Chigger, I would have thrown it away and started again. It was

fairly clear what the appeal of living in a fantasy world was to him. I

think we got off on a bad footing because, during a break from our

downstairs D&D session I came up to see what was going on in

the games upstairs, the ideal respite from playing a role playing game

being to watch one played.

The

players had just entered a bar. Twisted music spilled from a band of

aliens, drinks were dispensed on anti-gravity pads and strange

piratical adventurers lay around on padded seats, according to the DM.

Of all the scenes in Star Wars that capture people’s imagination it

seems to be the one in the bar that sticks in the mind most and, along

with laser duels between space ships, it was this one that most

frequently appeared in games of Traveller.

I

think this shows that a lot of what we were searching for in Dungeons

and Dragons was a taste of the exotic, to believe that the world was

full of surprising and fascinating possibilities and people, Han Solo

or Aragorn sipping strange drinks in the shadows rather than Chigger

munching on a Trio and trying to use words that you didn’t know.

Chigger,

even for a wargamer, had an arrogant attitude. For a start, only a

select few were allowed to play Traveller that day – Chigger said he

thought it best that the Grammar school boys should play it first so

that everyone in the game would be ‘on the same intellectual level.’

He

also, and this is in my view the mark of a bounder, seemed willing to

patronise my mum. On our wall we had a picture of Gainsborough’s Blue

Boy, complete with moulded plastic gold effect frame. In our family

this was referred to as ‘Little Boy Blue’ and, to tell the truth, I had

no idea of its real title or who painted until about five minutes ago

when I looked it up.

This

may sound like a hideous piece of decoration and in fact it was a

hideous piece of decoration but remember, this was the seventies. Given

the alternatives on offer it was a triumph of good taste.

Chigger

clearly didn’t think so.

‘Oh

that is nice, Mrs Barrowcliffe,’ he said on entering the front room,

‘is it real?’ He said this with a sort of snigger in his voice. Chigger

was labouring under two misapprehensions here. One was that my mother

was as easy to dominate as the younger boys he chose for his friends

and the second was that she wouldn’t pick up on his sly sarcasm.

‘I

like it,’ she said, ‘and if you don’t, you know where the door is.’

I

think Chigger was a little taken aback by my mother’s directness and he

spent the rest of the day in a sort of smirking attitude designed to

restore the face he’d lost with the other boys.

I

was embarrassed by this though, incredibly, not by Chigger but by my

mum. I didn’t want her offending my new friends and, while I could see

that Chigger was being in some way snide about the painting I was more

interested to find out what was wrong with it than in being angry that

he was disrespectful towards my mum. If I’d had to take a stab at why

he didn’t like it I would have said – in my words of the time – that it

was a picture of a pouf or that it was an obvious choice as lots of

people had that painting. He was an older D&Der and so, to my

set of values, more important to please than my own mother. I was going

to write that I resolved to have a more disdainful attitude to popular

art in future but it wasn’t exactly a conscious thing. I just know that

I started looking at things in a different light after that.

The

problem for me was that I couldn’t exactly tell what was meant to be

awful and what was good. To be on the safe side I started looking down

on everything.

Chigger,

it seemed to me, was just the most extreme example of an attitude

shared by most of the older wargamers, one of lofty disdain.

I

was on the receiving end of a lot of this disdain. I could have seen

through it and wondered exactly what they had to be so arrogant about,

I could have felt the rejection and the unpleasantness and vowed that I

would never make anyone feel like that myself. Instead, I started to

copy them.

Despite

my mum’s early tangle with Chigger he ran his grammar-school only game

of Traveller in my parent’s bedroom.

This

exclusivity went down poorly with Porter and Hatherley but there was

nothing they could do about it. Despite using my mother’s alarm clock

to represent a spaceport, he didn’t think I should be allowed in the

room.

‘We

need to concentrate and can’t have spectators, especially little twerpy

ones,’ he said, ‘this room is for Traveller players only, please leave.’

I

don’t know why but I did. It was, after all, my house. It was nothing

to do with him being older, it was as if the authority of owning such a

cool game gave him power over me.

Downstairs,

however, a conflict that was about to define my life was taking shape.

Andy and Billy were going head to head for the first time.

The order of the adventuring party was represented by miniature

figurines – this is known as the marching order. The problem was that,

in the excitement of a battle people often forgot to move the little

soldiers. This mean that we were in a position where the action of the

game was neither represented nor not represented by the figures.

The

rules are hugely unhelpful here. The Greyhawk supplement notes that

figures are ‘sometimes useful’. And sometimes not.

As

I recall, a trap had been triggered by the third member of the party,

causing the character to fall into a pit of poisoned spikes. We had a

thing for poisoned spikes then. As we became more sophisticated our

taste in traps would proceed through snakes to crushing rooms to the

insides of giant carnivorous plants to time loops that would make the

character endlessly repeat some action.

The

dungeon was at the time being run by a pleasant grammar school boy

called Neil Collingdale who had doubtless arrived under the impression

he had come to my house to play an interesting and diverting game

rather than to have the very terms of his existence questioned and

everything he believed held up to ridicule and contempt.

Collingdale

’s mistake was to be slightly inexact. He can’t be blamed here. I think

that a team of the country’s finest legal minds specifically employed

for the purpose of being exact might have found themselves ‘slightly

inexact’ under the scrutiny of Crowbrough and Porter.

‘Right,’

said Collingdale , ‘this wizard falls into the pit. Whose character is

that? He’ll have to make a saving throw.’

A

saving throw is a staple of the game. The trap goes off and the DM has

ruled that, unless you shake more than a 14 on a 20 sided dice you fall

in. He’ll then shake to see what damage the spikes do to you and then

you’ll have to make a saving throw against the poison or you’ll be

paralysed, dead or - as happened at one game I played at a D&D

convention – turned Welsh. This sort of thing appealed to the

uber-prattish, Monty Python inspired sense of humour of many gamers at

the time.

In

fact, one edition of White Dwarf magazine, discussing the various sorts

of dungeon it’s possible to run, included the category ‘The Silly

Dungeon’ populated ‘entirely with humour in mind’. Recommendations for

this humour included giant SS killer penguins, thieves in black fetish

leather armour and homosexual pink Kobolds. I never found this sort of

stuff funny, not from any PC reason but just because, well, it isn’t

funny.

‘Ha

ha, Porter, you’re in the pit!’ I said, because it was Andy’s magic

user who had ended up there. Porter gave me a look like aged spaniels

do when you suggest removing their dinner half finished.

‘That’s

not me,’ said Andy.

‘Who’s

the wizard figure, then?’ said Collingdale .

‘The

wizard figure is me but I’m not third in the party. That was Billy,’

said Porter.

‘No

it wasn’t,’ said Billy.

‘I

said I was going into the middle when I came out to that room,’ said

Andy.

‘You

didn’t move the figure to represent that, did you?’ said Billy.

‘We’re

not used to playing with figures,’ said Andy, which wasn’t strictly

true. It wasn’t untrue either. We normally started playing with figures

and then forgot about them, so he had a point.

‘It’s

not a matter of being used to it, it’s a matter of doing it. Some cats

aren’t used to crossing the road but they better do it right or it’s a

saving throw vs car tyre for them. You should have moved it.’

‘I

can’t reach it, can I?’ said Porter. He had a smidgen of the contempt

he normally directed at me but it was of a different quality with Billy

at that point, more like a teacher saying he would have thought an

intelligent lad would have known better. There was also the implication

that, had he been organising the game, the figures would have been in

an easily accessible position, despite the fact we were seated around a

large extended dining table with a camping table at both ends to make

it bigger.

‘You’re

as near as I am,’ said Billy.

‘You

didn’t move yours.’

‘Because

I was happy with its position, QED,’ said Billy. That was a first. I’d

never heard Porter QEDed before. ‘You didn’t move your figure, Dave,

were you happy with your position?’ Billy was going by the barrister’s

maxim of never asking a question that you don’t know the answer to.

Dave hadn’t fallen into the pit so of course he was happy with his

figure’s position. Anyone who hadn’t fallen into the pit was happy with

their position.

Dave

was Dave Fearnly, my super-quiet second-year friend.

If

Dave had been happy with the position of his man he wasn’t happy with

the position between Porter and Crowbrough. He made a sort of grunting

noise that could be interpreted by either side of the argument as a

token of support.

In

the latter years of our play I attempted to bring a greater role

playing element into the game and asked each character to provide a

description of what they looked like and their general demeanour

whenever I ran a dungeon. Some were very inventive although you could

guess Billy was never going to say ‘a well toned bloke who’s a hit with

the girls,’ because Billy didn’t want to admit to himself that well

toned blokes are, on the whole, a bigger hit with the girls than chip

devouring fatties and Andy was never going to say ‘a self effacing,

rather timid and nervous priest who just wants to help people’. Dave,

for every single character he ever played said ‘he looks like a man in

a cloak’.

Sombre

monk? ‘A man in a cloak’.

Cheeky

thief? ‘A man in a cloak’.

‘Elf

warrior? ‘A man in a cloak’. Surely the elf warrior must look more like

an elf in a cloak, Dave. ‘This one looks more like a man.’

‘What

kind of man? Bald, hairy, tall, short, black, white?’

‘Just

a man.’

Dave,

I feared, was never going to be much help to the police if he witnessed

a robbery.

At

the time this seemed quite unremarkable, just another dose of

adolescent tunnel vision. We played with one chap, a Steven Wright if I

recall correctly, who used to have tomato ketchup on everything he ate

– I recall him putting it on a Kit Kat once. That didn’t seem

remarkable either.

‘Collingdale,

you heard me say that I wasn’t standing there didn’t you?’ said Porter.

Neil

Collingdale, oblivious as only a well brought up boy who has been

raised to believe everyone should be as nice as possible to each other

all the time can be, said ‘yes’.

I

don’t think he understood the pandemonium he would unleash. Porter sat

back with a smile. What this meant was that, where the argument as to

who had been in line for a spiking was originally confined to Porter

and Crowbrough it now spread to the whole table. Any of us were in the

frame, apart from Porter who had seemingly been given a free pass.

Billy

had, I think, an exaggerated sense of fairness, one of those attitudes

that look well on paper but can get you steamrollered in real life or

at least make your day to day dealings quite difficult. This, to him

was an abhorrence.

‘It’s

not me who was there,’ said Billy, ‘either the figures mean something

or they don’t.’

‘I

think we’ve just established that they don’t,’ said Porter with a

chortle. I chortled along with him and felt good to be sharing someone

else’s discomfort with Andy, rather than being the discomfited one

myself. Andy, as older boys will, shot me a look that said I should get

off his chortle and find something to chortle about of my own if I

wanted to chortle at all.

Some

situations, I think, require victims if any progress is to be made.

This was one of them. A trapdoor had opened, someone had to fall

through it. Unfortunately Collingdale didn’t see it that way. I think

he liked Billy and didn’t want to offend him. He was beginning to wish

he’d never mentioned this pit of spikes in the first place and,

ironically enough, he looked a little as if the floor had just fallen

away underneath him.

‘I

didn’t say that it was you,’ said Collingdale , trying to look as

though it was in control.

The

room erupted with shouts of ‘well it wasn’t me!’ and ‘I’m the one with

the bum-shaped hat, you can clearly see I’m at the back.’ ‘You’re not

the one with the bum hat you’re the slave girl.’ ‘My character’s male!’

‘Yes but we’d run out of figures and you said you didn’t mind having

your magic user represented by a slave girl until someone died.’ ‘I

said you shouldn’t mind having your magic user represented by a slave

girl, that’s very different.’

No

one there was actually living the possibilities of the game. The game

is a story and stories have beginnings, middles and endings. We didn’t

want an ending for our characters, just to go on and on undying and

ever more powerful. This is an unsatisfying way to play, like going

through a video game with all the cheats operating.

Porter

and Crowbrough were arguing like that was all they’d been made to do.

In fact, given their shapes and colouring it seemed that maybe they had

been designed to fight each other by some god with a taste for the

burlesque. Even the way they sat was different, Billy wide and

expansive, like father Christmas waiting for the next child, Andy more

contained - limbs tucked in to suggest the sort of crouch that precedes

a pounce.

‘What

is the point in having the figures at all then?’ said Billy, ‘wipe them

away,’ he made a dramatic gesture, ‘take them all away now.’ There was

always something theatrical about Billy. He looked like a Kabuki actor

displaying ‘brooding anger’.

‘The

point is that the dungeonmaster needs to be more attentive and

clearer,’ Andy, in common with all – well, men, really – could never

admit to a mistake. ‘A flaw in the system doesn’t mean that the system

needs to be completely discarded, only amended,’ said Porter.

‘This

is weak dungeonmastering indeed,’ said Billy, pointing to Collingdale ,

who looked appalled, like a well-bred English gent being accused of

spying for taking a few snaps near a Greek airfield.

‘It

is weak but that’s not my fault,’ said Porter, ‘we needed someone with

more experience. You’re not up to the job, Collingdale.’

‘Probably

his upbringing,’ said Hatherley, ‘liberal parents leaving him weak

willed. We should mark him with a suitable symbol.’

‘Pink

triangle,’ barked Dennis.

‘Go

and fetch Chigger,’ said Billy.

‘Hang

on,’ said Collingdale . This was a bit outrageous. It’s like being in

court (a lot of our D&D arguments reminded me of two rather

unsuccessful barristers slugging it out) and suggesting that you throw

out the judge if you don’t like the way the case is going.

Most

D&D books recommend that, if a player cannot accept a

dungeonmaster’s decision, the player should be expelled from the game.

That kind of presupposes that the dungeonmaster isn’t a boy who has

simply come for a pleasant day’s fun and the people to be thrown from

the game aren’t individuals of iron will to whom it is a matter more

important than life or death.

Chigger

was sent for. Most of us accepted that sort of thing. At that age you

think of yourself as an adult but you behave as a child and we were

going to the oldest boy there as a kind of appeal to a surrogate

parental authority.

Chigger

loved an argument, saw that it has sort of been settled in Andy’s

favour, so he took Billy’s side and said that Andy should have moved

the figures. This put us back at square one.

‘Well

if you can’t play the game properly, Andy, then perhaps you should

choose something less mentally demanding,’ said Chigger, who loved to

say things like that.

Porter

looked like he was about to explode. He didn’t appear to like being on

the receiving end of this stuff very much.

‘I’m

used to games where the DM’s on the ball,’ he said. Collindale very

soon after took up Badminton, I believe, where the disputes are more

straightforward. It’s in or it’s out, a shuttlecock, isn’t it? No one

announces half way through that they thought everyone was agreed they’d

given up using the net.

‘I

am appealing to simple logic,’ said Billy.

‘The

logic in this case is far from simple,’ said Porter, ‘the DM needs to

make a decision right now and the correct one.’

‘You

can’t change the rules half way through,’ said Billy, ‘it’s like saying

‘I don’t like gravity, I should be allowed to float around. Anything

else you don’t like? The relationship between Time and Space, perhaps,

maybe we should have that altered for you.’

I

don’t know what became of Neil Collingdale but I suspect a career in

the diplomatic service would have been rewarding.

‘You’re

saying Andy definitely falls into the pit Billy?’

‘I

am,’ said Billy, on clouds of wrath.

‘I

don’t’ accept…’ said Andy.

‘Right,

The spikes were illusions and there’s a magic wand at the bottom.

Andy’s in the pit undamaged by the fall,’ said Collingdale . This is

the thing about being a dungeonmaster you can, if you want, just make

things up.

‘I

test the wand,’ said Andy.

‘He

just said he wasn’t in the pit,’ said Billy.

‘And

you just said I was,’ said Andy.

‘You

don’t understand, do you Porter?’ said Crowbrough, ‘I’m giving in to

your argument.’

‘Oh

no, Crowbrough,’ said Porter, ‘it’s you who’s won.’

And

off they went again, arguing the opposite of what they’d been saying

ten minutes before.

I

think we got to about the fourth room of around 50 we could have

explored of that dungeon before everyone had to go home. I didn’t know

it at the time but this sort of argument was going to go on for a long

time – nearly four years. In fact it became, to paraphrase Michael

Moorcock, an eternal argument that seemed to exist independently of

whoever was actually arguing. At times it seemed we weren’t people at

all, just expressions of a position, parts of a machine that could be

worn out and removed but would just be replaced by new parts to keep

the engine of disagreement running.

I

would have chosen to be on Billy’s side in these confrontations but, I

was to learn in the coming years, you don’t always choose your side in

a row; sometimes it chooses you.

Want

to read more of The Elfish Gene? Click

here to find out more and buy the book.